Common Funding Mistakes when Scaling

Many successful entrepreneurs advise startups to always raise as much possible to grow quickly, stay ahead of the competition, and offset the unexpected. They reason that, as your business grows, you’ll recoup the initial expenditure and minimize the risk of future dilution. That can be true.

Raising a Lot to Fuel Rapid Growth Isn’t a Strategy

Having extra funding can help offset rising expenses as you scale. But simply raising as much as you can isn’t a sound strategy. Raising capital has consequences. If you seek a high valuation and receive a large sum upfront, you’ll typically be deemed a higher risk and have to give up more equity. Many startups accept the trade-off, believing that a large round of financing will meet rising expenses as they scale.

The problem is, many expenses that occur during rapid growth are tied to cash flow in ways most founders don’t anticipate.

If you don’t have enough cash flow circulating, you’ll need to raise more funding just to stay alive. But raising a new round when you’re short on cash puts you in a precarious position.

Growth and Cash Accessibility

As you scale, expect that operational challenges and unforeseen delays will impede your cash flow.

Choices that worked for a competitor may not work for your company because of your cash flow situation. Decisions that worked for you in the past may not work as you scale. When scaling, take time to understand cash flow implications and, as you scale, rethink your business model with cash flow in mind.

As a professor of business administration at HBS, investor and board member on dozens of companies, Shikhar Ghosh has observed that many founders conflate raising a significant amount of venture capital or getting a high valuation as validation of a business plan and move forward following the same business plan and behaviors. But as you scale, past behaviors stop working effectively and often processes are strained and break.

It’s easy to grow your company to death and a surprisingly high number of entrepreneurs don’t realize this.

Shikhar Ghosh

Scaling Costs Aren’t Multiplied Costs

When calculating how much funding you need to scale, don’t simply multiply past expenditures. Accurately forecasting how much you need to raise may require you to question and possibly abandon past behaviors that worked. Scaling rarely occurs in a precise, predictable linear fashion as illustrated in this scaling experiment gone awry.

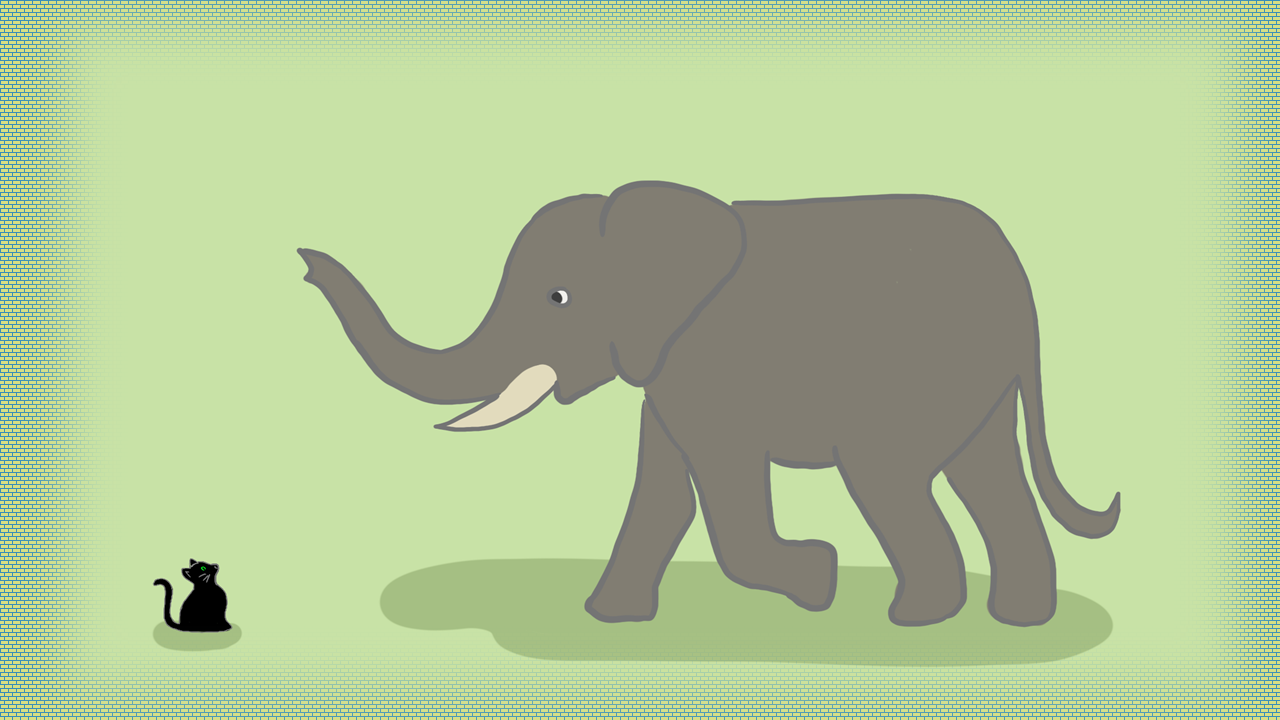

Dr. L. J. West wanted to induce highly aggressive behavior that male elephants exhibit during musth, a time when their testosterone surges. In 1962, years before PETA was established, he planned to inject Tusko, a 14-year-old Indian elephant living at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Oklahoma City, with LSD. In other controlled studies, his team had administered .02 mg of LSD to cats, “without irreversible effect.”

Reasoning that they could determine how much of the drug they needed by multiplying the volume they used on cats, the scientists increased the volume of LSD administered to 297 mg to account for Tusko’s 7000-pound body mass. Within minutes, the elephant collapsed and began convulsing.

Twenty minutes later, to counteract what scientists now know was a massive LSD overdose, West injected large amounts of an anti-psychotic then pentobarbital sodium. Tusko died a few minutes later. Why?

Animals possess different sizes, weights, densities, and metabolic rates, making it challenging to compare doses between species. The scientists botched their attempt to calculate the amount of the drug they needed to safely scale from the mass of a cat to an elephant. Entrepreneurs can draw parallels from this tragic example.

Pitfalls of Counting on Projected Revenue

Most founders determine the amount they need to raise and make plans based on growth revenue. But including projected revenue in your cash management plan can backfire. Often, a significant delay exists between the time an invoice is issued and when you receive payment. It’s not uncommon for large corporations to take 60 days to remit payment to accounts receivables, so “don’t factor that revenue into your plan until the money arrives. Most founders miss this,” Ghosh notes, “they forget that at the start, it’s primarily about cash flow.” At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter if invoices will be paid tomorrow if you can’t pay your bills today.

Realistically, your maximum financing needs will extend beyond the point when you start generating revenue. The unfunded time between your date of first cash flow positive and maximum financing needs is known as the fume date—an estimated point for when a business will deplete its cash and run on fumes until it collapses. When allocating how to spend the capital you raised, “factor in cover unpredicted expenses and what it takes to survive past your fume date.”

Running on Fumes

Rajesh Yabaji, co-founder of BlackBuck, a B2B tech logistics startup that launched in India, in April 2015, discovered this the hard way. Within one year of launching, the company had signed over 120 clients, hired over 1,000 employees, and established operations in over 200 locations. Its revenues were on track to exceed the forecast by 300 percent. From the outside, their meteoric growth suggested they’d become a unicorn and VCs rushed to invest.

But by June 2016, Blackbuck had only $5 million left of the $25 million they’d raised 6 months earlier. What happened? BlackBuck showed revenue growth, but most of its funds were tied to working capital and not accessible.

We introduced incentives on getting new revenue without looking at cash flows properly. We knew our business was scalable, but we had not tested the sustainability. Ironically, rapid growth threatened to kill the company.

Rajesh Yabaji

Learn how BlackBuck’s co-founders turned the situation around and, by fall 2018 raised $27m in a Series D led by Sequoia.