Navigating a Deal before You Sign a Term Sheet

You received a term sheet from a VC. Understanding the tradeoffs and implications of the terms you’re offered can prevent critical misunderstandings and optimize your level of control and cash upon exit. How do you assess the offer and navigate a term sheet, making sure you’re getting the best terms and payoff for your company? HBS faculty, serial entrepreneurs and investors identified 3 different angles from which you need to examine terms.

3 Considerations when Reviewing Terms

- Risk mitigation

- Growth expectations

- Valuation

Not all offers are created equal. Terms can most dramatically affect the best- and worst-case scenarios and aligning with investors’ terms can make or break the future for most founders.

Risk Mitigation

Risk Mitigation

Most VC investments return little to no profit. To offset the high risk of investing in startups and provide downside protection for other companies in their portfolio, VCs need to see the potential for extremely high returns on their investments. Most VCs look for opportunities that will generate $50 to $100 million within 5 to 7 years.

Shikhar Ghosh, a founder, CEO, and chairman of 8 tech companies, who worked closely with several VCs in the past decades explains, “at the time of initial investment, VCs can’t predict which ventures will be winners and which will fail to meet expectations,” so returns earned by a small percentage of ventures within a portfolio must be high enough to offset the lower-performing ones.

Average VC Portfolio Performance

- Over 60% of the startups ultimately failed and were liquidated at an amount less than the original investment level.

- Only 8% of the startups accounted for 70% of the overall returns of the portfolio.

Ghosh, who also invests in promising startups and, as a professor of business administration, now coaches emerging entrepreneurial leaders at HBS’s Arthur Rock Center for Entrepreneurship, summarizes, “in essence, the winners pay for the losers, so even a risky set of investments can lead to substantial returns.”

Equity and Explosive Growth

VCs offset the high risk of investments by expecting 2 things equity and explosive growth: Accepting equity allows investors to reap potentially limitless returns. Unlike debt investors, who receive a capped return on investment before equity distribution, return on equity has no limits. If a company financed with $10 million of debt sells for $10 million, the debt holder re-collects the $10 million, while the equity holders receive nothing. Imagine the same company sells for $100 million. The debt investors would receive their $10 million back—but that’s it. The equity holders, however, have $90 million to share.

While debt investors want to see steady returns and stability, VCs search for opportunities that show high potential for explosive and rapid growth to offset the losses incurred from most of the investments in their portfolio.

Growth expectations

Growth expectations

An investor’s expectation of growth may not align with your growth goals or business model. Working with hundreds of entrepreneurs, Ghosh advises founders to carefully consider the source of their investment.

“One of the largest mistakes that founders make is accepting a deal from investors whose expectations don’t match their business model. If your vision for growth doesn’t align with your investor’s expectations and you fail to meet high return goals, your VC can cut off your funding. “

~Shikhar Ghosh

Aligning expectations

In other words, who you take money from matters almost as much as how much you raise. Misalignment of growth expectations can quickly sour a founder-investor relationship and impede raising subsequent rounds. Christina Wallace and Alex Nelson learned this lesson the hard way. When the HBS graduates co-founded Quincy Apparel—a company that designed bespoke work clothes for women—in 2011, they raised $1m from angel investors and venture capitalists. No similar e-commerce companies existed for customized women’s clothing at the time; because of the higher risk associated with their venture, investors were unwilling to infuse large amounts.

As the co-founders crafted a roadmap for growth, they faced serious operational challenges. Despite its struggles, Quincy Apparel showed slow growth with the potential for eventual success. But because the company failed to demonstrate the kind of rapid growth and lucrative returns that VCs need, when Wallace pitched for a Series A, VCs declined to invest. Without that subsequent round of funding, the company closed. Wallace recalls how misaligned expectations contributed to Quincy’s failure.

“I learned that who you take capital from matters. Understanding their motivations and pressures matters, because it will affect what advice they give and what pressures they then exert on you.”

Christina Wallace

Tranching

Most VCs specialize in a market, bringing not only financial resources to the deal but considerable operating experience and connections. In many cases, having witnessed mistakes other companies like yours have made, VCs are uniquely positioned to help you achieve your goals. But, as Wallace experienced, terms empower investors when misalignments arise—practices like tranching allow VCs to curtail funding for companies that fail to meet their high return goals within a specified time.

Instead of releasing the total funding amount at once, most VCs release funds in increments or “tranches” as a company meets the milestones outlined in the term sheet.

Tranching reduces an investor’s overall risk by unlocking funding at key de-risking points. Tranching poses a common misalignment between VCs and entrepreneurs because slow and steady growth may not satisfy VCs.

A founder who sees slow but steady growth may be surprised to learn that, if she doesn’t meet the aggressive expectations for growth outlined in the term sheet, the VC has the right to withhold future funding. Know and meet your milestones. Failing to unlock funds necessary for growth can propel a company into a slow death spiral, making it even less likely to stay on target and meet the next milestone. This affects valuation, which provides another angle for approaching a term sheet.

Valuation

Valuation

Don’t fixate on a “true” valuation of your venture. The market determines your company’s monetary value. But don’t forget that key aspects of valuation, like equity split, can become part of the negotiation.

Assigning Value

Calculating very different valuations provides another common misalignment between founders and VCs. How do VCs assign value to a venture? After analyzing cash flow, assets, liabilities, and market transaction comparables, VCs do extensive market research weighing your timing, past achievements, and future roadmap against valuations given to similar ventures at your stage. Despite these tools and calculations, valuations are partially subjective—they don’t follow a strict scientific formula, as Ramana Nanda, a financial expert, and professor of business administration at HBS, who advises startup ventures on their financing strategies points out.

“Valuation is a negotiated outcome and the result of the relative bargaining power of the counterparties.”

Ramana Nanda

The key lies in the fact that, as a startup, your bargaining power is typically low until after you prove your hypothesis.

How Valuations Misalign

Imagine you own a rapidly-growing company that manufactures and sells an upscale, vegan, caffeinated drink. Containing high levels of protein, it appeals to health-conscious US consumers and fills a gap in the beverage market. Based on similar niche drinks, you estimate 5 more years of rapid sales growth—in the range of 10% to 20% per year—before settling down to long-term growth. Basing your calculations on predictions, you arrive at a valuation of $25 million, requiring $2.5 million in investment.

After several encouraging conversations with a mid-sized VC firm that specializes in early-stage startups in high-end consumer markets, you receive a “founder-friendly term sheet.” To your surprise, the firm offers you $3 million at a valuation of just over $6 million–nearly a quarter of the valuation you expected. What do you do?

At this stage, many founders, having a firm valuation in mind, become disappointed or irate.

How can VCs and founders consult the same numbers and draw different financial conclusions? In this example, by building a financial forecast “bottom-up” you estimated the weekly volume that you could achieve in different types of retail accounts, based on recent sales in existing accounts. Assuming the drink would sustain momentum, you projected $50 million in sales in two years.

But to grant a high valuation, VCs need concrete assurance, not speculations. Investors, looking at your company in the context of the market, know that even companies with strong track records have only a 1 in 3 or a 1 in 4 chance of making aggressive growth projections. And the beverage industry is fickle—of the roughly 2,000 new beverage brands that launch each year, only 3 or 4 reach sales of $100 million. Most fail to scale or run out of cash within two years. Doing your own market investigation, you discover that the high risk of your venture lowers the valuation considerably. It turns out that $6m was at the high end of normal in the market.

When Investors’ Valuation is Much Lower

Before walking away from a valuation that’s lower than you expected, Ghosh and Nanda emphasize that entrepreneurs should remember: Investors think primarily in terms of future dilution when calculating valuation.

VCs calculate how much money you need now to reach the valuation, decrease your risk and minimize dilution if you raise subsequent rounds. Even during an up round—when the value of a venture increases between financing events—raising subsequent rounds of investment can dilute equity. But a substantial increase in the overall value of the venture offsets the dilution of equity. Entrepreneurs are deemed successful when they continue to increase the value of their equity ownership, even if their overall equity decreases.

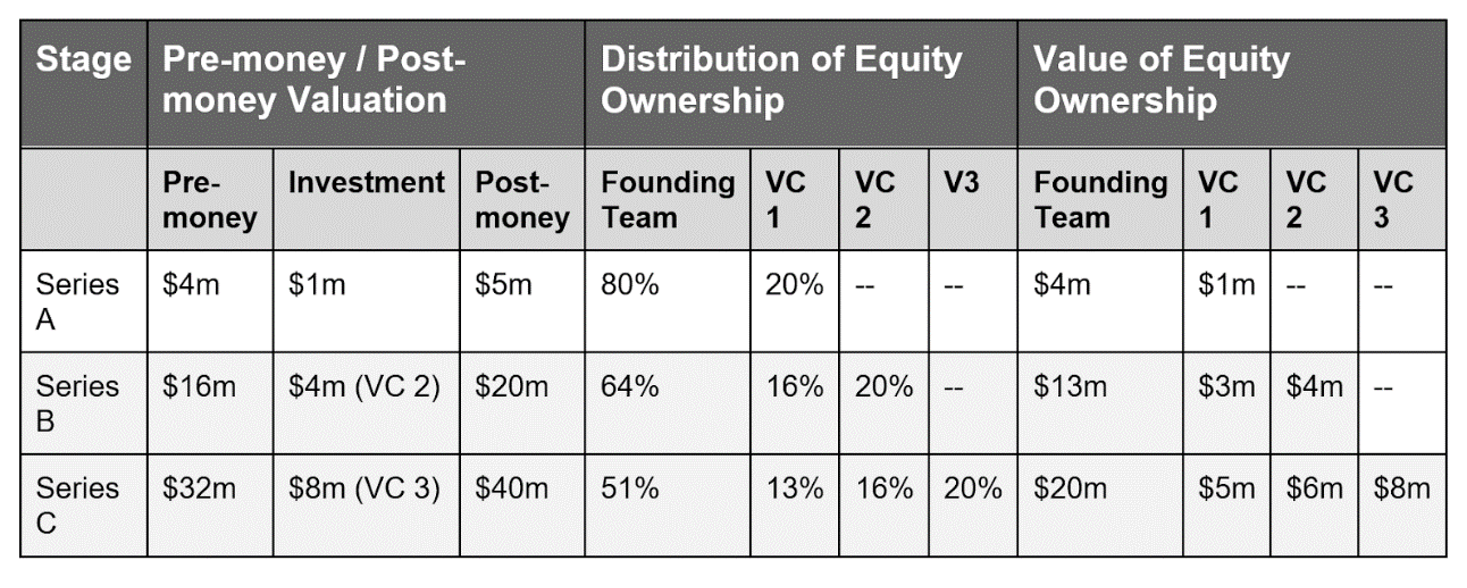

Sample Cap Table, Series A

As the sample cap table below illustrates, in Series A, the founders gave up 20 percent of the company for $4m. By Series B, an up round, 20 percent of the company was valued at $16m.

Founders often covet a high valuation and develop an emotional attachment to a specific number. Aiming for a lower valuation may sound counterintuitive or feel anticlimactic. But, in the long run, a lower valuation may save you from facing a flat round or from dealing with a down round in subsequent financing events.

Because valuation is subjective and initial valuations depend on many unverified predictions, it’s important to remember that receiving a lower initial valuation is not necessarily a bad thing.

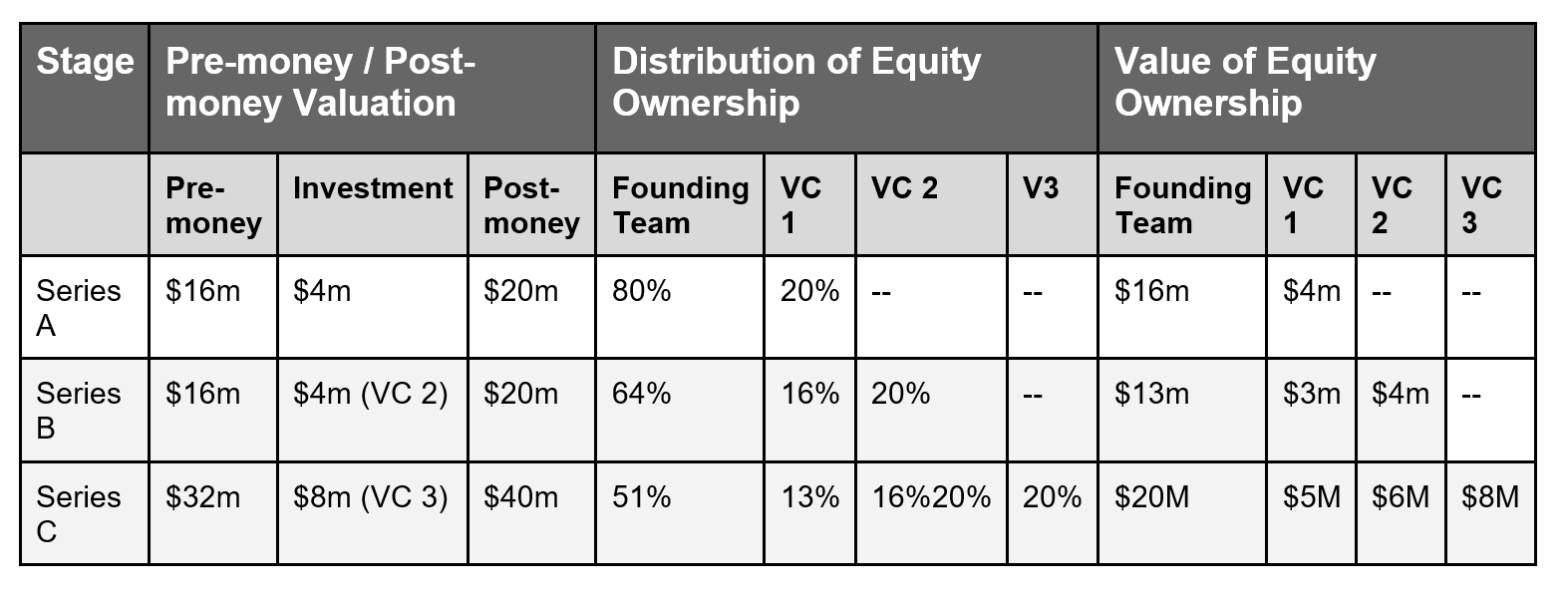

Sample Cap Table for Flat Round, Series B

The sample cap table below shows a flat round—raising money at the same valuation as the previous round—for Series B.

The company’s valuation remains at $16m, but the founding team’s equity value has decreased from $16m to $13m.

While not ideal, as the example shows, you can recover from a flat round. Rebounding from a down round—being forced to raise money when your value is below your last valuation—is far trickier. Even if a company survives a down round, the founding team has significantly decreased its leverage and influence for subsequent rounds.

It’s better to avoid a down round by accepting a lower valuation.

Negotiating Equity

Even offers with the same valuation and investment amounts may impose drastically different expectations. Babak Nivi and Naval Ravikant, who co-founded AngelList in 2010, recommend that before signing a deal, entrepreneurs should solicit at least 2 independent, competing offers from VCs who invest in startups at their stage. They remind founders that, while the market determines your company’s value and equity is tied to valuation, you can increase your chances of securing more favorable equity splits by building leverage by creating a market for your shares. When negotiating equity, Nivi reflects, “I would strive for 70–20–10 (founders, investors, option pool), depending on how much you’re raising. The more you raise, the greater your dilution. And I would settle for 60-25-15.”

After soliciting competing offers and choosing a firm, be prepared to negotiate but realize: many investors may not budge on their initial valuation.

If you focus exclusively on valuation over other terms, you may end up at an impasse. Nanda stresses to entrepreneurs, “many of other terms, including those that define expectations about performance, establish roles and decision-making authority, and stipulate consequences, can—and should—be negotiated.”